Listen! The night is filled with noises.

Listen! The night is filled with noises.

Leaves whisper. Wind sighs in the pine trees. Maybe an owl hoots, or a fox yips.

And in spring, ringing high over all the other sounds, you might hear a faint peep peep peep. Near forest ponds, meadow marshes, and puddles in the backyard, you can hear it rising out of the dark: the love song of the spring peepers.

spring peeper

What are spring peepers? They’re tiny frogs, not much bigger than the tip of your thumb. But these little amphibians can make a huge noise.

Frogs spend the winter hibernating. Peepers sleep away the cold under logs or leaves, but in early spring they migrate to water. There, in a pond or swamp, on the first nights, the males begin to give their high, sweet call.

But why does the frog chorus tune up at night? Wouldn’t it make more sense for frogs to go looking for each other in broad daylight?

Unfortunately for frogs, they’re a favorite menu item for a lot of predators. So if a frog doesn’t want to end up as lunch, it makes sense to sing noisy love songs under cover of darkness. And frogs don’t need daylight to find each other. Even if the female frogs are far from the pond, and even if it’s pitch dark, they can hear the males’ song with their sharp ears.

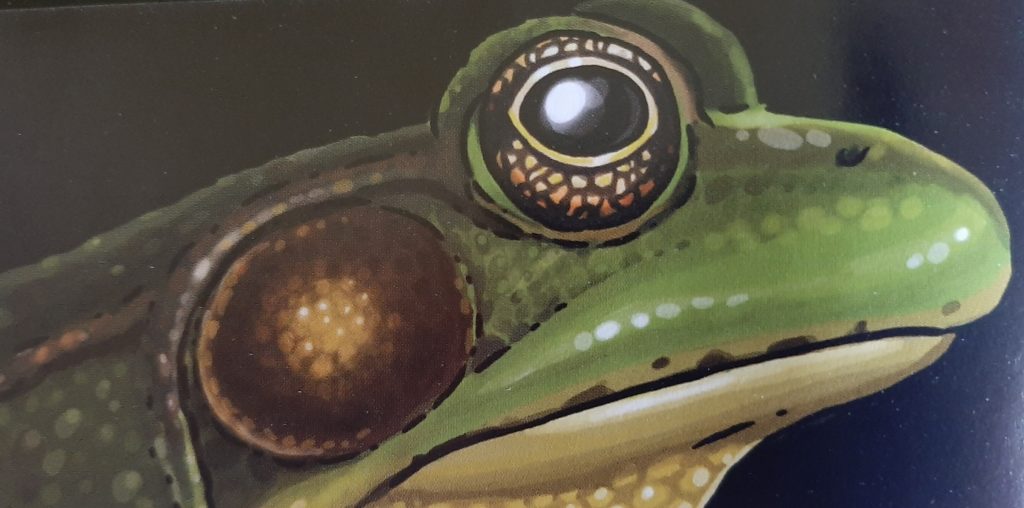

Wait a minute—frogs have ears? Actually, they do. But they don’t have ears that stick out from the head (external ears) like humans or dogs. Big floppy ears would slow frogs down while swimming. Frogs have a flat disk of skin behind each eye, called the tympanum, or ear drum.

Sound waves hit the surface of the eardrum, making it vibrate like the top of a drum. These vibrations travel along the auditory nerve and on to the brain. The brain decodes these signals as sounds.

A female peeper can find another peeper on the darkest night, even if they start off half a mile apart. That’s a long way for an inch-long frog to travel! But hopping along, a few inches at a time, she tracks the sound until she locates the exact lily pad or blade of grass that the male is sitting on.

There are many species of frogs, and some of them look a lot like each other. It can be hard even for herpetologists to tell some species from others. For example, leopard frogs look a lot like pickerel frogs. But each species has its own special call. Leopard frogs sound like a door creaking. Pickerel frogs sound just like a person snoring. Even in the dark, the female frog can’t mistake one for another.

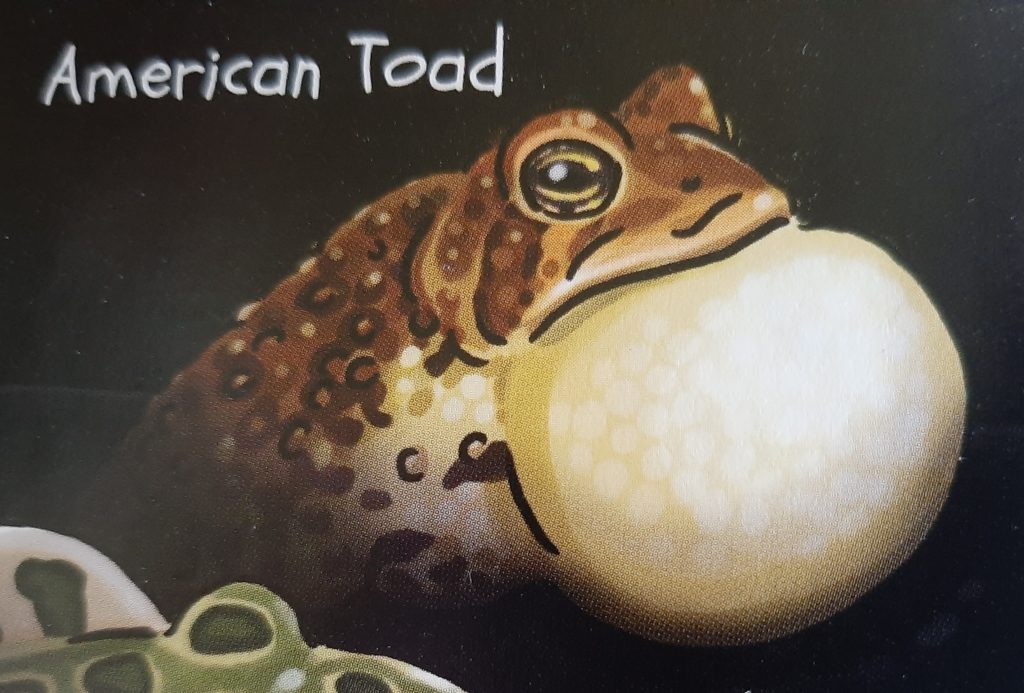

There’s an incredible range of frog noises, and these musical amphibians keep up the concert all through the spring. After the early peepers begin, wood frogs join in, sounding exactly like ducks quacking. Then green frogs go “plunk!” like a banjo string, while American toads sing a beautiful high-pitched trill. Late in the spring, bullfrogs shout “jug-o-rum” in deep voices.

On a spring night, grab a flashlight, and head outside to anywhere there’s water. Some frogs will even mate and lay eggs in mud puddles, or on swimming pool covers. If you hear frogs calling, move closer—but be quiet. If the frogs hear you coming, they’ll clam up. Shine a flashlight out over the surface of the water. You may see tiny sparkles: the eyes of a frog reflecting light back at you.

Every spring night is filled with the noises of many conversations.

Listen!

To learn more about nature at night, please check out my book:

To learn more about nature at night, please check out my book:

Wait Till It Gets Dark: A Kid’s Guide to Exploring the Night.

by Anita Sanchez and George Steele, illustrations by John Himmelman.

Recent Comments