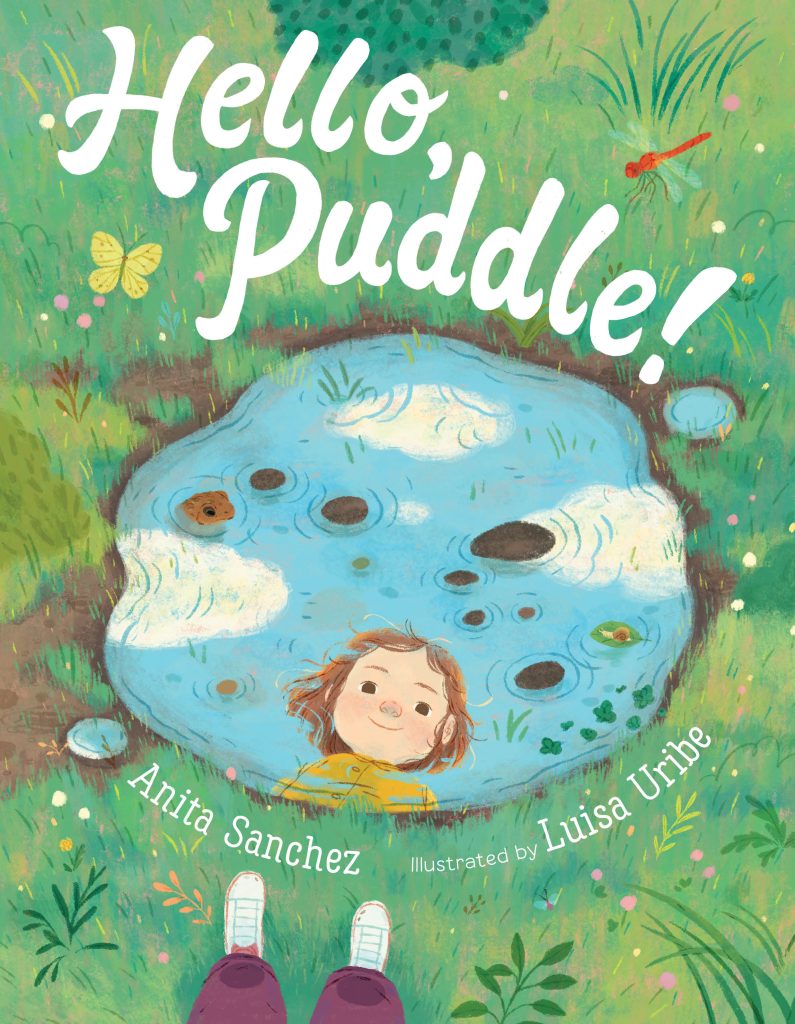

A nonfiction picture book exploring a deceptively simple but unexpectedly crucial resource for wildlife: puddles! This lyrical, gorgeously illustrated nonfiction picture book is perfect for young science learners and nature lovers.

A nonfiction picture book exploring a deceptively simple but unexpectedly crucial resource for wildlife: puddles! This lyrical, gorgeously illustrated nonfiction picture book is perfect for young science learners and nature lovers.

Educators’ Guide with Student Activities

Hello, puddle! Who’s here?

A normal everyday puddle may not seem very special. But for a mother turtle, it might be the perfect place to lay her eggs.

For a squirrel, it might be the only spot to cool off and get a drink when the sun is shining down in July.

And for any child, it can be a window into the elegant, complex natural world right outside their window.

With lush, playful illustrations and fun facts about the animals featured, Hello, Puddle! is a joyful celebration of the remarkable in the ordinary, and the importance of even the most humble places in fostering life.

From the Book:

Hello, puddle!

Who’s here?

Tadpoles wriggle and squiggle

Toad eggs will hatch in a few days, and tadpoles will quickly turn into tiny toadlets.

Seeds sprout

Grasses, wildflowers, and tree seedlings soak up water from moist mud, sending out leaves and roots.

Swallows loop-the-loop

Barn swallows grab a beakful of mud. They’ll raise their babies in a dried-mud cradle.

Mother turtle scratches and digs

A female turtle needs soft soil to dig a hole and lay eggs. Warmed by the sun, baby turtles will hatch out weeks after she’s back in the pond.

Ducklings dabble

Ducks scoop up puddle water with their beaks to strain out tiny bugs and plants.

Snails slowly saunter

Moist, slimy skin helps snails soak up air to breathe.

Robins splish and splash

Birds love a good bath! Clean feathers help them fly their best when it’s time to find food—or dodge a predator!

Research in the Mud

So there’s this mud puddle. It sits at the bottom of my driveway—a long country driveway that dips in the middle and rises again, and at the lowest point there’s always this puddle. In the driest days of August, it’s just a skim of mud. But in spring the puddle fills with rain, and sometimes threatens to rise over your ankles—it gets deep enough to guard the house like a moat. The Fed Ex folks and mail carriers hate it. People with freshly washed cars hate it. My entire family hates it, and frequently beg me to yield and get the driveway blacktopped already. But I won’t.

Because butterflies love my puddle.

In summer I watch butterflies flittering to the puddle, drawn to its muddy margins as though to a blossoming rosebush. They come to rest, slowly fanning their kaleidoscope wings. As if they were sitting on petals, they uncurl their long tongues and sip—not nectar—but muddy water, rich in the minerals and nutrients they need.

Another reason I can’t possibly blacktop the puddle is the robins. They splash and fling water over their heads and stretch out dripping wing feathers and wiggle their tails in glee. Honestly, do wild animals ever just kick back and have fun? Sure looks like the robins are purely enjoying themselves.

Then there’s the skunk. One foggy morning, as I gazed out my office window, pondering a topic for a new book, I saw a skunk daintily lapping from the puddle. Then he stretched, I swear he yawned, and waddled off to his den for a nap after a long night of digging beetle grubs.

All that summer, as I struggled to come up with a topic for a nonfiction book on wildlife, I idly watched the puddle, laced with snail trails, dipped into by dragonflies, visited by toads.

I was trying to think of a creative idea for a picture book. Something about wildlife habitat. I wanted to write about a place that nurtures a broad diversity of wildlife, that provides all the crucial components of habitat: water, food, shelter, a place to breed. Should I write about rainforest, jungle, desert? The bottom of the ocean, the tundra, the Arctic? All those remote and exotic habitats that most kids will never actually see…

And then I looked at the puddle again.

So I researched mud puddles. And my search led me to piles of books and journals and websites galore. I learned about the importance of ephemeral pools for amphibian reproduction, and how frequent bathing improves feather quality and enables birds to better escape predators. I read scholarly articles with titles like “Mineralogical and Textural Characteristics of Nest Building Materials Used by Mud-nesting Hirundine Species,” explaining why declines in populations of barn swallows are directly linked to lack of a readily available source of mud for nesting. I read about wasps rolling mud into balls and carrying it off to use in creative nest-building. I learned about puddling behavior in Lepidoptera—who knew “to puddle” could be a verb?

(And in the end I had way, way, way too much information, and had to make the usual agonizing decision: what to leave out and what to put in. Of course, you can always fit some of the good stuff into the back matter.)

But in the end, the really crucial research—the research that counted most—was just my idle window-gazing, watching the puddle through the seasons. The book was created out of my own first-hand experience and observation. Every animal mentioned in the text—toad, skunk, butterfly, mud-dauber wasp, snail, deer—I watched as they used the rich habitat of my driveway to find food, water, or shelter.

That’s the thing with research. You’re always doing research. You just don’t always know you’re doing it.

Recent Comments