Flowers are beautiful–at least, most humans seem to find them so. There’s something about their scent, their symmetry, their color, that entices us to come closer. But plants produce flowers, not for human enchantment, but for the bewitchment of pollinators. Flowers are publicity.

Flowers are beautiful–at least, most humans seem to find them so. There’s something about their scent, their symmetry, their color, that entices us to come closer. But plants produce flowers, not for human enchantment, but for the bewitchment of pollinators. Flowers are publicity.

Bees are common pollinators, of course, but there are also flies, bats, hummingbirds, moths, beetles…thousands of species of potential pollinators: organisms that spread one plant’s pollen to another accidentally, in their quest for nectar. And plants have evolved thousands of ways to attract pollinators.

Some plants use their size, their shape, or their vivid color, to attract those pollinators that see well. Other flowers attract pollinators who rely on scent more than vision, so their flowers are less conspicuous, to the eye, but send out a strong smell. We are most familiar with garden flowers that have a sweet, insect-attracting fragrance, but there are flowers that have a horrid stench: a graceful red trillium has a delightful aroma of rotting liver which very successfully attracts the flies and carrion beetles that pollinate it.

But how do dandelions do it? Each individual dandelion flower is tiny, hard to see. And dandelions don’t have a strong smell. How to attract a pollinator to a flower that is the size of an eyelash?

Think of a lot of people lost in the wilderness, trying to attract the attention of a passing rescue helicopter. If the people scattered, the pilot would never spot them no matter how much they waved their arms or jumped up and down. But if the group all stand together, they have a much better chance of attracting that pilot’s notice as he glances down–particularly if they create some sort of symmetrical pattern that stands out against the random growth around them. And their chance of attracting attention is better yet, of course, if they’re all wearing T-shirts of a brilliant color that is a strong contrast their green background.

Okay, so grouping a lot of little flowers on the end of a stalk is a way to attract pollinators. But why not just have one big flower that a pollinator can’t miss?

Well, one big flower of, say, bloodroot produces one big seed, one chance to get its genes into the gene pool. But if anything happens to the bloodroot flower before the seed ripens, that’s it. End of story. One shot at immortality. Perhaps it would be better not to put all the eggs in one basket? A plant has more chances to reproduce if it has more than one flower. But remember the energy price tag! A plant must photosynthesize to create energy to reproduce. One big flower is expensive, draining a plant’s hard-earned resources; two are twice as much of an investment.

bloodroot flower before the seed ripens, that’s it. End of story. One shot at immortality. Perhaps it would be better not to put all the eggs in one basket? A plant has more chances to reproduce if it has more than one flower. But remember the energy price tag! A plant must photosynthesize to create energy to reproduce. One big flower is expensive, draining a plant’s hard-earned resources; two are twice as much of an investment.

One tiny dandelion flower can produce one seed; two hundred flowers, crowded on a single head, can produce two hundred seeds. But the plant would have to put a huge amount of energy into a stalk that was strong enough to support two hundred big showy flowers. The more flowers the better, but if you don’t want a support stem the size of a street lamp, the flowers had better be small.

So there you have it: many small, lightweight flowers, brightly colored, all clustered in a symmetrical pattern on the end of a long stalk, held high above the grass. That’s the dandelions’ basic pattern, and the pattern that is echoed by all its many relatives. Flowers are publicity, and dandelions excel at the marketing game.

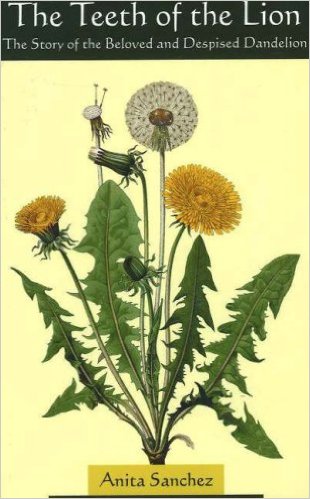

For more dandelion lore and ecology, please check out my book The Teeth of the Lion: The Story of the Beloved and Despised Dandelion.

For more dandelion lore and ecology, please check out my book The Teeth of the Lion: The Story of the Beloved and Despised Dandelion.

Recent Comments