photo by Jordan Harrison

What’s going on with the giant blob of seaweed that’s heading for Florida? What’s it made out of?

It’s a massive belt of a seaweed called Sargassum. Looking down towards the water from the deck of a ship, Sargassum looks like flat, floating mats of weed. But below the surface, Sargassum creates a whole forest—upside down.

Think of a forest, with trees reaching up from the ground, spreading branches high into the air. Now flip that picture, and imagine trees hanging down from the sky. That’s what it’s like in the Sargassum forest. Sheltered in the downward-hanging fronds of seaweed is a complex, layered ecosystem as rich as the one found in a tropical rainforest.

In that deep ocean where there are no rocks to cling to, the seaweed becomes the land. Strands of golden weed are crusted with barnacles, sponges and tubeworms, the kind of creatures that usually cling to rocks. Creatures that can’t swim, like crabs, have to hold on to their seaweed patch, living their whole lives on a tiny floating island.

Living in the Sargasso Sea are many species found nowhere else in the world. They match the seaweed precisely and are almost invisible in it. If you’re a sea creature who is small, defenseless, and tasty, the best way to survive is to blend in with whatever is all around you. The Sargasso fish, named for the seaweed it lives in, looks exactly like a floating bit of weed. Protected from predators, the Sargasso fish uses finger-like fins to wriggle through the seaweed, preying on even smaller fish.

photo by Maria Belen Caro

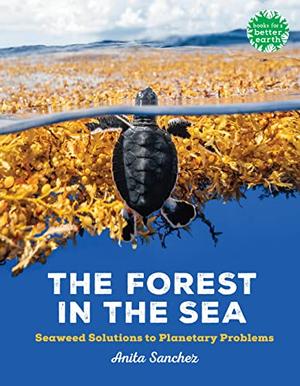

Many small creatures, especially young ones, use the upside-down forest as a nursery—a place to grow safely, protected from predators. Baby sea turtles, after hatching on land, swim hundreds of miles to reach the Sargasso and grow up in its protection. They’ll hide in the shelter of the forest until they grow big enough to increase their chances of survival in open water.

Eels are water creatures that look like worms or snakes, but they’re really just a skinny kind of fish. They live in freshwater ponds and streams, sometimes for years, but they always return to the Sargasso where they were spawned. No one knows how eels find their way to their birthplace, hundreds of miles through the trackless sea. Once sheltered by the thick seaweed, female eels lay millions of eggs. After hatching, baby eels hide in the Sargassum for years before heading back to the land their parents came from.

photo by Maria Belen Caro

The Sargasso Sea is also a giant playpen for baby fish. More than a hundred species of fish lay eggs there, and the babies hang out in the calm, warm water. Some fish live in the weed all their lives, like the pufferfish, that can inflate itself into a spiny porcupine when threatened. Others leave the forest once the young fish have grown large enough to risk open water: cod, tuna, halibut, swordfish, and marlin. Many of these species are fish the people of the world depend on for food.

Just as hawks hunt in the sky over a land forest, predators hunt in the deep water beneath the seaweed. Sharks cruise below the Sargassum, searching for prey. Whales crisscross the waters under the Sargasso on their yearly migrations, and depend on the rich feeding grounds they find there. Some whales, like orcas and sperm whales, hunt for fish, squid, and bigger prey. Other whales, like humpbacks and right whales, feed on plankton. When these animals eventually die, their bodies nourish all sorts of decomposers: crabs, worms, insects, bacteria.

photo by Craig Lambert

From top to bottom, the Sargasso Sea is brimming with life. And all of those organisms, from the tiniest shrimp to the largest whale, depend on seaweed for their existence.

For more about seaweed, please check out my book The Forest in the Sea.

Far out and full of secrets…