At the age of 81, it looked like Claude Monet was all washed up. His eyesight was dimming, failing—the worst possible calamity for a painter. But he was working on a project—and he had to finish it.

Beginning at the age of seventy, cataracts had slowly begun to thicken over his eyes. They blurred his vision and changed his perception of color, making it hard for him to perceive greens and blues. His world of sparkling waterlilies faded to a muddy yellow fog.

Surely it was time to quit. He’d had a good life—unlike most of his contemporaries, he’d achieved fame and modest fortune. He was a respected artist, his paintings beloved by millions during his lifetime.

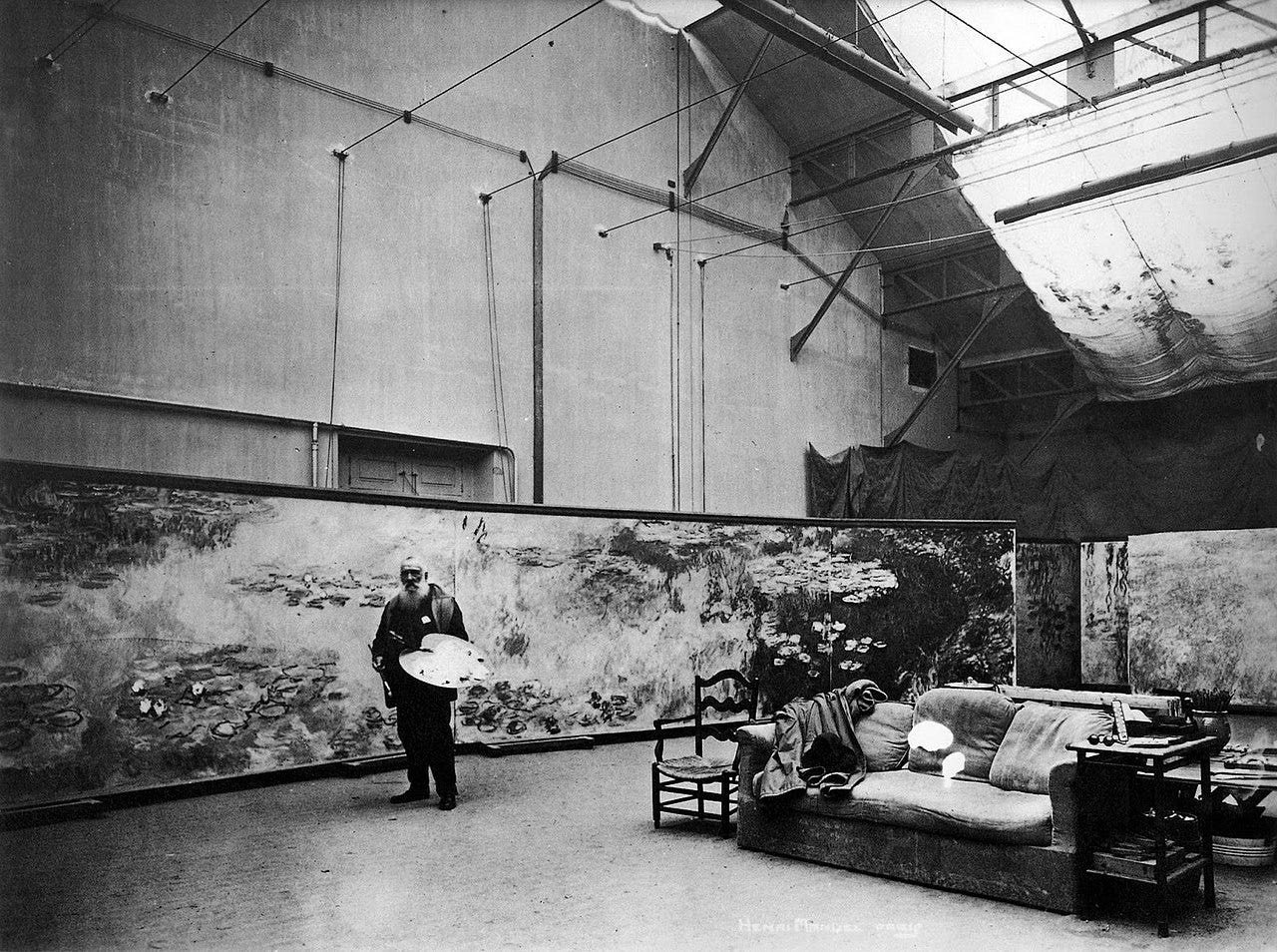

But he went on painting. He was working on what he called his Grandes Decorations: a series of water lily paintings. He had a specific purpose in mind: to donate this work to the people of France, to help them heal from the trauma of the Great War. He’d painted waterlilies before, of course. But this time the old man thought on a colossal scale. Each painting was to be at least six feet high and more than fourteen feet long, and he envisioned dozens of them, strung together in a wide horizon of water and floating flowers.

His family begged him to rest, to relax, to enjoy his retirement, to take care of his health. He went on painting.

Most of the Grandes Decorations are in the Louvre now, but we’re fortunate that a few of the panels are in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. On a recent trip, I spent a long time in front of the waterlilies. They reminded me that age can be more passionate than youth. That physical disabilities can be turned to unexpected advantage. And that the terrible knowledge that this is your very last chance can depress and weaken you—or inspire you.

Recent Comments