Karl, Get Out of the Garden!: Carolus Linnaeus and the Naming of Everything

Charlesbridge Publishing

Honors for Karl, Get Out of the Garden!

School Library Journal starred review

John Burroughs Society Riverby Award

Bank Street College of Education Cook Prize Honor Book

SONWA Award Notable Book

American Horticultural Society “Growing Good Kids” Award

Welcome to the Garden!

Is it possible to name every single thing in the world? Well, no, but Karl gave it a try! Karl, Get Out of the Garden! is a children’s biography of a scientist who was fascinated with nature. In his quest to name everything, Carolus Linnaeus invented a whole new language of science.

Why Name Things?

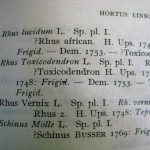

Rosa canina. Canis familiaris. Homo sapiens. Who thought up these baffling Latin names?

Binomial nomenclature is a key concept in science. It’s the way scientists know without a doubt which organism is which. The scientist who invented this classification system started out as a boy with a passion for plants and bugs.

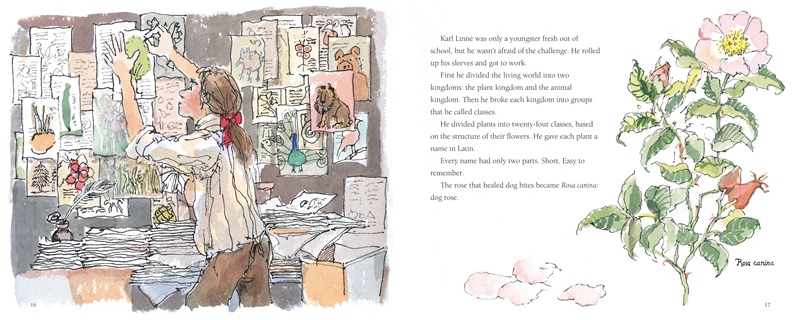

Karl Linne (better known by his Latin name, Carolus Linnaeus) was a mediocre student whose parents encouraged him to follow his heart. Karl studied botany and became a doctor, using plants for medicines. But which plants? In the 1700s, one plant might have thirty names. In order to avoid deadly mistakes, Karl invented the system of binomial nomenclature—in other words, he named things.

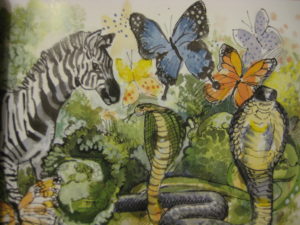

Karl named and classified more than twelve thousand types of plants and animals. Other scientists didn’t agree with his ideas, and Karl battled his critics fiercely. He also became a beloved teacher, leading eager students on twelve-hour field trips into forests and gardens he called his “living textbooks.” Today Karl’s work is used by scientists all over the world.

Karl named and classified more than twelve thousand types of plants and animals. Other scientists didn’t agree with his ideas, and Karl battled his critics fiercely. He also became a beloved teacher, leading eager students on twelve-hour field trips into forests and gardens he called his “living textbooks.” Today Karl’s work is used by scientists all over the world.

The book explains the difficult concept of scientific classification in clear and simple language, making it of special interest to science teachers. This book explains the reason for classification and shows how a little boy’s love of flowers and bugs led to a major scientific breakthrough. The text not only gives a lively account of the great naturalist’s life, but explains his magnificently simple system.

An Interview with the Author

Why is the book called “Karl, Get Out of the Garden!”?

Karl’s father loved nature and spent hours pottering in his garden—but Karl’s mother wanted her son to grow up to be a famous scholar. She pestered him to study and scolded him every time he sneaked out to the garden. But the secret trips to the garden became the basis of Karl’s lifelong love of nature and his scientific skills.

Why did you write about Karl?

As one of the world’s greatest scientists, Karl classified and named thousands of plants and animals, using forests and gardens as “living textbooks.” He invented a new language of science, and his work is the basis of the classification system used by scientists world-wide. Also he’s a really fun character to get to know!

Why is he important for kids to know about?

Karl Linne was a kid who hated school—but his father encouraged him to follow his heart. Karl turned his passion for nature into a life-long career, and he was eager to share his love of plants and animals with others. Perhaps he remembered how he had been bored in school, because he became a beloved teacher, leading rowdy, fun field trips into the garden and the woods.

How did you learn about Karl’s life?

How did you learn about Karl’s life?

Fortunately for historians, Karl loved to write and talk about himself. He wrote a lot about his childhood, from his earliest memories of flowers in his father’s garden. He also wrote hundreds of letters—warm and loving to friends, filled with insults to enemies–and we can learn a lot about him by reading his own words.

While researching this book I travelled to Linnaeus’s native Sweden and tried to follow in his footsteps, recreating part of his journeys to study and name plants and animals. I traveled north of the Arctic Circle, as Karl did, to visit Lapland. I photographed Karl’s famous garden in Uppsala, Sweden, the place where he wrote: “In my garden I live as happy as a king!” I also visited his beloved farm, Hammarby, and walked the paths where he led his students on their noisy field trips. In all these places, it was easy to imagine Linnaeus eagerly studying and naming his beloved plants.

While researching this book I travelled to Linnaeus’s native Sweden and tried to follow in his footsteps, recreating part of his journeys to study and name plants and animals. I traveled north of the Arctic Circle, as Karl did, to visit Lapland. I photographed Karl’s famous garden in Uppsala, Sweden, the place where he wrote: “In my garden I live as happy as a king!” I also visited his beloved farm, Hammarby, and walked the paths where he led his students on their noisy field trips. In all these places, it was easy to imagine Linnaeus eagerly studying and naming his beloved plants.

What other books have you written?

Like Linnaeus, I’ve always been fascinated by plants and animals no one loves. I’ve even managed to discover something good about poison ivy—it’s a major food for wildlife, especially for birds like robins, bluebirds and cardinals. Leaflets Three, Let it Be! The Story of Poison Ivy is a picture book which introduces the youngest explores to this scary but important plant. My next book was In Praise of Poison Ivy: The Secret Virtues, Amazing History, and Dangerous Lore of the World’s Most Hated Plant, a nonfiction book for adults.

I have a book coming from Houghton Mifflin called ITCH: Everything You Didn’t Want to Know About What Makes You Scratch. It’s about the science of itching, and some of the world’s most irritating—but fascinating—creatures: lice, bedbugs, fleas, cactus, mosquitoes, and fungus.

Other books coming up are: Wait Till It Gets Dark (Globe Pequot) about scary but incredible nocturnal animals like owls, bats, tarantulas, and Gila monsters.

Rotten: Vultures, Beetles and Slime: Nature’s Decomposers (Houghton Mifflin) is about all the amazing ways nature turns death into life: bacteria, dung beetles, sharks, and worms.

What places have you traveled to? What’s the wildest thing you’ve done?

I love to adventure in wild places around the world. I once rode a camel in the Sahara desert, and I’ve snorkeled coral reefs in the Kingdom of Tonga in the South Pacific. I visited an elephant orphanage in Sri Lanka, and watched baby elephants being bottle-fed.

In Karl’s native Sweden, I took a 20-hour train ride to the far northern wilderness where Karl studied plants. I loved the birch forests, fir trees, and the eerie glow of the Northern lights.

In Karl’s native Sweden, I took a 20-hour train ride to the far northern wilderness where Karl studied plants. I loved the birch forests, fir trees, and the eerie glow of the Northern lights.

Omnia mirari etiam tritissima!

(Find wonder in everything, even the most ordinary.)

–Carolus Linnaeus

Karl found wonder in everything in nature. He especially loved to wander through his g arden. He planted more than three thousand different kinds of plants!

arden. He planted more than three thousand different kinds of plants!

Karl used his garden as a living textbook to teach his students about science.

He planted plants from all over the world:

Some of them were beautiful exotic flowers like the Passionflower. Passionflowers are from South America. They’re vines that wine up the trunks of great trees in the rainforest. Karl loved the colors of flowers. This passionflower’s blossoms are blue as the sky and Karl named it Passiflora caerulea. Caerulea means deep blue, and comes from the Latin world for sky.

Some of them were beautiful exotic flowers like the Passionflower. Passionflowers are from South America. They’re vines that wine up the trunks of great trees in the rainforest. Karl loved the colors of flowers. This passionflower’s blossoms are blue as the sky and Karl named it Passiflora caerulea. Caerulea means deep blue, and comes from the Latin world for sky.

Many of the plants Karl studied were ones we see almost every day. But to Linnaeus they were exotic species, recently imported from the mysterious New World. Corn! Tomatoes! These were rare and exciting new plants.

Tomatoes were planted in the flower gardens because of their pretty red fruit. But no one ate them—they might be poisonous! Other plants in the tomato family, like nightshade, are poisonous, so everyone assumed tomatoes must be, too. Many Europeans believed tomatoes were deadly poison for centuries. Solanum lycopersicum means “wolf peach.” Tomatoes are part of the nightshade family, and people believed that nightshade was one of the magical herbs used by werewolves and witches.

Zea mays. Corn was first planted as a crop by the indigenous peoples of Mexico 10,000 years ago. It was a major food source for many native American tribes. To Linnaeus it was a wonderful new plant, full of exciting possibilities for feeding hungry people. When Karl named corn, he used the original Indian name. The Taino people called corn mahiz and he kept that name, only he spelled it mays.

Zea mays. Corn was first planted as a crop by the indigenous peoples of Mexico 10,000 years ago. It was a major food source for many native American tribes. To Linnaeus it was a wonderful new plant, full of exciting possibilities for feeding hungry people. When Karl named corn, he used the original Indian name. The Taino people called corn mahiz and he kept that name, only he spelled it mays.

Karl had a high hedge around his American plants to make sure no one stole these valuable specimens. He wanted people to admire them but not get too close!

stole these valuable specimens. He wanted people to admire them but not get too close!

Karl’s favorite pet was a raccoon sent to him by a friend who visited America Raccoons aren’t found in Europe, so Karl had never seen one. He soon fell in love with the strange animal with the bandit mask.

A Plant Afraid of Drowning

Linnaeus often named plants after colleagues, choosing the name based on some quality in their personality. He named Tillandsia, a genus of plants that apparently survives without water, after a botanist named Elias Tillander, who detested the ocean after a near-drowning.

A Stubborn Plant

A student of Linnaeus’s, Peter Forsskål was stubborn and determined, and after his tragic early death Linnaeus named an especially hardy plant Forsskaolea tenacissima.

Recent Comments