A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

From the Book:

Chapter 1: The Science of Poop? You’ve Got To Be Kidding!

Poop? Ugh! What could be more revolting, useless, and downright disgusting?

But in nature’s endless and complex cycles, there’s no such thing as waste. The poop of wild animals isn’t just a big pile of pollution. Poop—or scat, as wildlife biologists call—is full of surprising power. It can be food. It can be shelter. It can be life. And okay, it can be smelly.

The seeds that are sometimes carried in scat can create whole forests. Scat can be fertilizer for oceans and prairies. And scat is like a coded message that the animal leaves behind. Sometimes animals use it to “talk” to other members of their own species. But sometimes, scat is talking to us.

For anyone who wants to learn about wildlife, scat is like a website filled with information. Humans can use scat to learn about the animals—where they go, what they eat, even what mood they’re in. Scientists are struggling to find ways to help wildlife, and scat can reveal clues about how animals are responding to climate change threats like temperature changes, drought, and habitat loss.

| Scat Science: Ways to Say Poop

We call it all sorts of things—doo, poo, droppings, and other words you can’t say in polite company. But scientists use the term scat to describe the excrement of wild animals, as opposed to human waste or farm animal’s manure. The word dung usually refers to the big moist splat of large herbivores (plant-eaters) like cows or bison. The poop of insects, tiny as grains of pepper, is called frass. And the waste of flying creatures like birds and bats is called guano. |

Just What Is Poop, Exactly?

No matter if it’s human or hippo, parrot or puppy, whale or worm—every animal’s digestive system basically works the same way. It’s a long tube where food goes in one end and waste comes out at the other.

The food goes into the mouth, and is chewed, mashed or scrunched into tiny bits. Then the mush is swallowed down into the gut where powerful chemicals and bacteria attack it. The food is dissolved by stomach acids, chewed on by bacteria, and broken down into smaller and smaller specks until it’s a slushy liquid. As the slush passes through, the body absorbs some of the good stuff—nutrients, vitamins, and minerals—soaking them up like a sponge. A lot of the water that was inside the food is soaked up too. Some of the useful stuff goes into the body—everything else comes out the other end.

In One End, Out the Other

A bug’s digestive tract might be half an inch long; a horse’s is a hundred feet long. A whale’s innards could be longer than a football field! Your intestines, if you spread them all out in a straight line, might be thirty feet long! Of course, no one is thirty feet tall—the intestines are all coiled up inside your body.

Ick! The stuff that comes out doesn’t look like food anymore. Or does it? Sometimes there are bits that don’t get digested. If the critter is a carnivore (meat eater) there might be leftover scraps of bones, fur, or feathers in the scat. If it’s an herbivore, there might be bits of bark, stems, or seeds. (Remember this—it’ll be important later on.)

Smelly Signpost

If you happened to be walking your dog along a trail and saw a pile of scat in the middle of your path, you’d hastily jump over it and go on your way. But your dog would want to sniff it, and sniff and sniff aaaand sniff some more. That’s because to the sensitive nose of non-human animals, scat reveals a ton of information: what kind of animal has passed by, how long ago, what species.

An animal can’t send a text, make a phone call, or put up a sign for another animal that might be miles away. But the animal can poop, and that’s what it does. Often the pile is in open, obvious spaces—the middle of a trail, a clearing in the woods, on top of a log—where someone else might bump into it hours or days later.

Scat scent can help a young animal find its mom, or avoid predators. Or scat can send a strong message to rivals: This is my territory, stay away. An animal might use scat to announce that they’re looking for a mate: Hey, come on over this way!

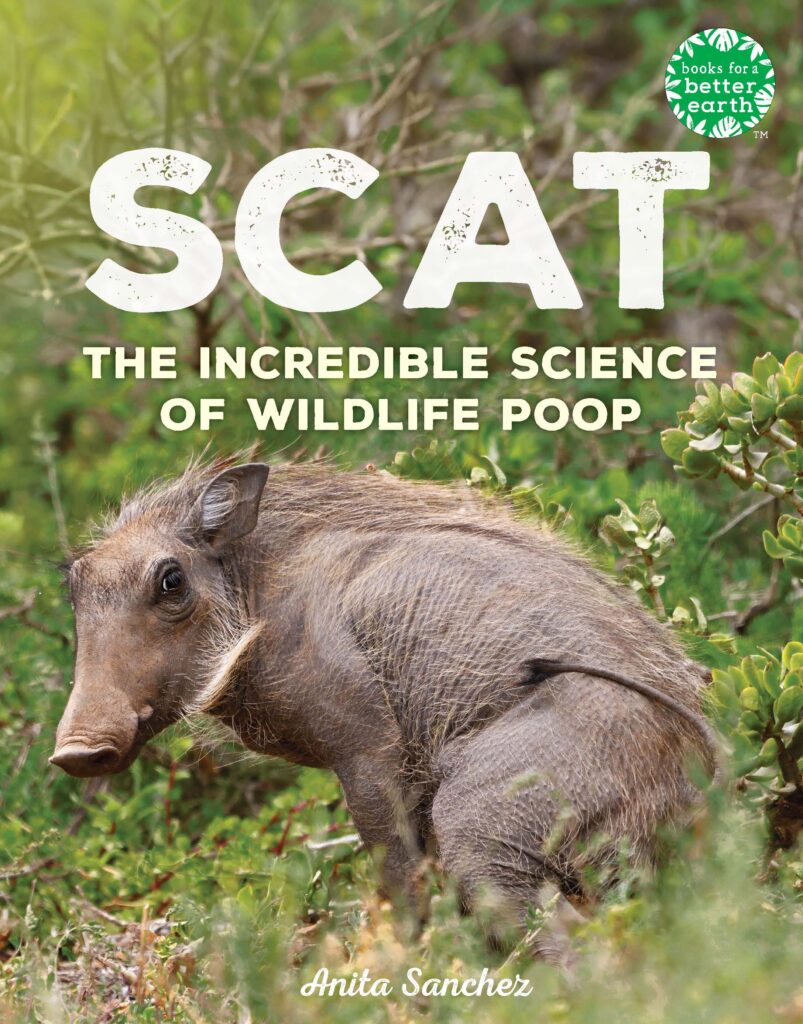

Photographed in Addo Elephant Park, South Africa.

| Sidebar: Scat Science

Why Does Pet Poop Smell Bad, But Wildlife Scat Doesn’t? Ugh! Your nose tells you that your dog has made a mistake indoors…or that it’s time to clean the litter pan. No doubt about it, pet poo smells awful. But wild animals don’t stink up the great outdoors in the same way. Wildlife scat is filled with odors, but they’re mostly not the kind that human noses notice. Wild animals eat food they find in the natural world, that their ancestors have been eating for millions of years. Pets, on the other hand, are fed a human-designed diet of things their stomachs aren’t evolved to eat—corn, seaweed, potatoes, ground-up fish scraps–all kinds of odd bits and pieces go into commercial pet food (If you don’t believe me, read the ingredients on a bag of kibble sometime.) This artificial diet is often not well digested, so that bits of it pass through the stomach and aren’t broken down till they reach the end of the digestive system, called the colon or the large intestine. This process produces gases like methane and hydrogen sulfide, which result in smelly poop. |

Are You Ready to Take a Closer Look?

Are You Ready to Take a Closer Look?

Poop or scat—whatever you want to call it—isn’t the same thing as garbage. Scat has an unexpected but crucial part to play in nature. In fact, it’s not too much to say that poop is powering our planet.

As it has for millions of years.

photos by Sumarie Slabber, Kathy Raffel, Gary Seloff

Recent Comments