It’s not like I don’t have anything else to do. There are dishes to be washed, rugs to be vacuumed, gardens to be weeded. Litter pans to be changed. But sometimes when I have an odd moment, I busy myself with a household chore that’s less than urgent but deeply satisfying: I shelve books.

It’s not like I don’t have anything else to do. There are dishes to be washed, rugs to be vacuumed, gardens to be weeded. Litter pans to be changed. But sometimes when I have an odd moment, I busy myself with a household chore that’s less than urgent but deeply satisfying: I shelve books.

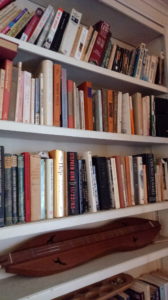

I have approximately a zillion books, lined up on shelves all around the house, and for years I stubbornly resisted putting them into any order whatsoever. I liked the odd jumble of Darwin next to Peter Rabbit next to Sherlock Holmes next to a geology textbook next to poetry by Emily Dickinson. I got a kick out of putting odd bedfellows together: Little Women rubbing elbows with Henry VIII and James Herriot, Caligula cozying up next to Hellen Keller, Winnie the Pooh facing down D’Artagnan.

But finally I got tired of having to search through endless shelves in an endless quest every time I wanted to locate one particular book. I decided to find some way to organize the mess. But how?

Dewey decimalize? Too mathematical. Alphabetize? Too random. Categorize—all the science books together, all the poetry, all the biographies? Too dull.

So then I got the brilliant idea. A time line. Start with prehistory, then Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, then the Middle Ages, and so on and on and on into the future. Whether the book is fact, fiction, or poetry, it goes in its appropriate place on the time line. Simple.

Only, of course, it isn’t simple. This system calls for a lot of tough decisions. Some books like, say, A Tale of Two Cities, span several decades, but the key events are during the French Revolution, so it goes in the last edge of the 1700s. But how about something like Roots, which spans early 1700s to mid-1900s? I settled for picking my favorite part, the childhood of Kunta Kinte, and putting it in the mid-1700s, where he sits next to Johnny Tremain and Benjamin Franklin, Mozart, and Linnaeus.

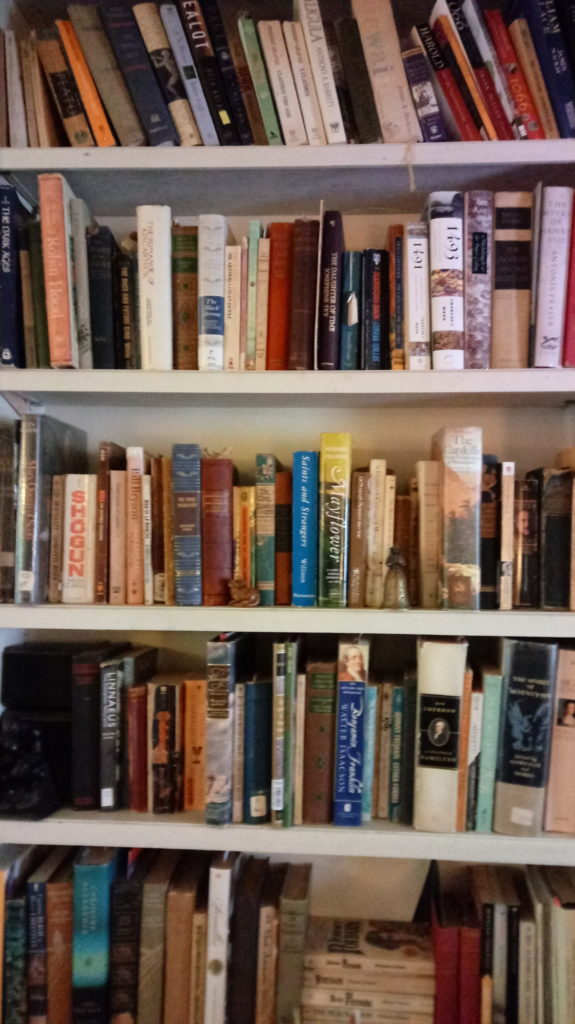

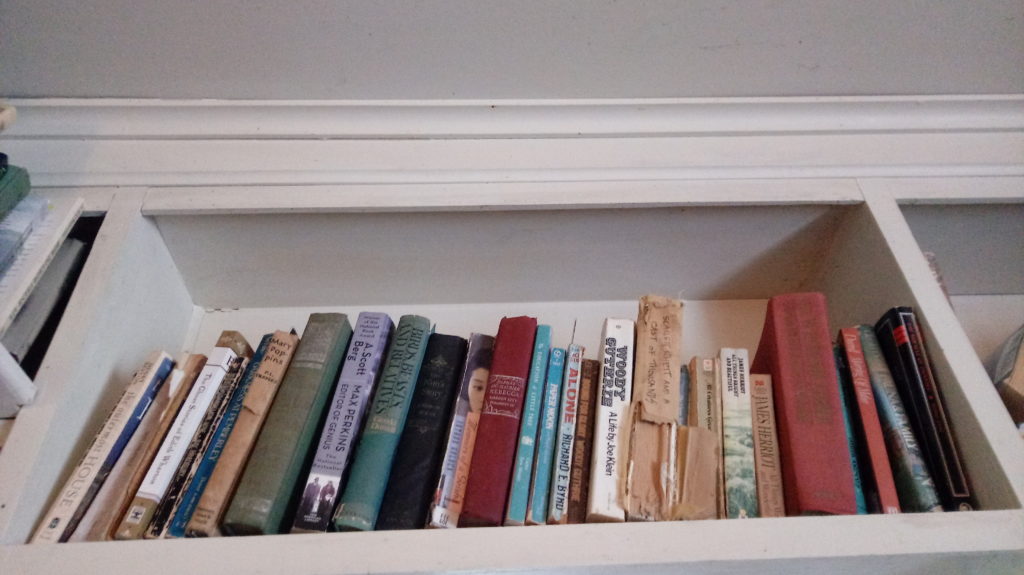

It’s endlessly fascinating, this way of seeing history visually stretched out on shelves. In the 1920s all the polar explorers, (for some unknown reason I’m fascinated by polar exploration) come together in more or less the same era. Amundsen sits in uneasy truce with Scott, followed by Shackleton. Charles Lindbergh is next to poor Mallory who died attempting to climb Mount Everest. Odd to see the frivolous party animals of The Great Gatsby rubbing shoulders with these obsessed adventurers.

The Thirties have an interesting cast of characters lined up, from Woody Guthrie to James Herriot to Memoirs of a Geisha, and then all of a sudden it’s World War Two, with everything from sober military history to thrilling spy novels to the horror of The Boy In the Striped Pajamas. And then it’s the Fifties—a biography of Gandhi next to Exodus, and the Sixties, Martin Luther King and Airport, and so on.

But the hardest dilemma was: where to put fantasy books? What about science fiction? Well, books like The Martian Chronicles and The Hunger Games are set in a somewhat recognizable future, so they go on the bottom shelf at the very end of the time line. The Chronicles of Narnia books begin in the 1940s in our world, and then go into a fantasy realm from there.

But how about Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones, with no temporal link to our world? I finally gave up and put them on their own shelf–a realm apart for stories that are timeless.

Other exceptions to the timeline rule are science texts and field guides, self-help, and those big old coffee-table type books that just won’t fit on a middle shelf.

So there it is. Fiction and nonfiction rubbing shoulders through the long shelves of time, starting with early humans in Quest for Fire and ending with The Martian. There are a few empty spots here and there…maybe I should buy some more books…

Recent Comments