While out West they’re getting all excited about their superbloom of California poppies, we Easterners are enjoying our own superbloom. Ours is reliably annual–we don’t have to wait a decade or so for rain. Wet or dry, the dandelions bloom just the same.

While out West they’re getting all excited about their superbloom of California poppies, we Easterners are enjoying our own superbloom. Ours is reliably annual–we don’t have to wait a decade or so for rain. Wet or dry, the dandelions bloom just the same.

Why is this? What is there about this one partucular species of plant that makes it bloom so lavishly, and in the one place we don’t want it to–our lawns?

After an injury, wise mothers apply band-aids. Nature’s band-aids are the tough, aggressive plants called seral species. These are hardy plants that thrive in the conditions that occur after disaster, springing up on soil that seems as desolate as a war zone.

Dandelions are a seral species. They move into a new habitat quickly, like medics rushing on to a battlefield. Each dandelion seed is a dry, hard, brown speck an eighth of an inch long, known in botanical terms as an “achene,” with minuscule barbs arranged along each edge of the seed. Hanging under its parachute, the pointed seed gently comes to earth and touches down like a practiced paratrooper, feet first. The umbrella-shaped parachute remains erect, spread protectively overhead, and each touch of breeze makes the seed tilt back and forth, embedding itself more firmly with every movement. The seed slowly penetrates the soil, working its way in deeper, like a barbed arrow.

At the first touch of moisture, dandelion seeds germinate with explosive speed. Growth begins at the soil surface or near it, when the temperature is at least 50 degrees F, though light and warmth increase the rate of germination, which is at the max at about 77 degrees F. Tiny rootlets snake their way between grains of soil, in search of water and nutrients which flow back up the lengthening roots to power the growing plant. The web of dandelion roots pry the close-packed soil particles apart, effectively roto-tilling the earth, while at the same time they hold the loosened soil in place. A long taproot sucks calcium and other minerals from deep in the ground, and carries the nutrients upwards to the leaves. Soon the first layer of dandelion leaves decomposes into a nutrient-filled compost. Dandelions enrich the soil for other plants: they fertilize the grass.

Like determined folk in covered wagons, seral species are pioneers; they blaze a trail which others, less hardy, can follow. And like all pioneers, they fundamentally change the nature of the place they come to inhabit. The newly fertilized and loosened soil is colonized by other plants: grasses are usually the next to move in, then shrubs and trees. Inevitably, the sun-loving seral plants fade away in the shadows. The dandelion prepares the way for its own extermination.

Like determined folk in covered wagons, seral species are pioneers; they blaze a trail which others, less hardy, can follow. And like all pioneers, they fundamentally change the nature of the place they come to inhabit. The newly fertilized and loosened soil is colonized by other plants: grasses are usually the next to move in, then shrubs and trees. Inevitably, the sun-loving seral plants fade away in the shadows. The dandelion prepares the way for its own extermination.

That’s how nature heals natural disasters. The seral species, the dauntless pioneers, are drawn to the ecological land of opportunity; they move in and then are replaced by other species until the armor of green is restored, in the age-old natural process known as succession.

But a lawn is not a natural disaster. It’s a human-made disaster. As soon as the seral species move in to start the healing work, the mower roars by. The process starts all over again, with the dandelions sprouting again overnight. But then another mower goes by. It’s a state of permanent catastrophe.

A lawn is, of course, a pleasant place. The very word “lawn” has a casual, lazy ring to it, bringing to mind hammocks and iced tea, softball games and summer vacations. A lawn, to most humans, is a congenial spot to sit down and rest for a while. But there’s a proverb that says that if it’s God who invented grass, it’s the Devil who invented lawns.

These days, a lawn seems like the most natural thing in the world, a green stretch of nature among the city streets and suburban housing lots. But there’s nothing less wild than a lawn. It’s a crop-field just as much as a field of wheat or soybeans, and as quick to disappear without constant human intervention. A lawn is continually being altered by humans: ecologically speaking, it’s a permanent catastrophe. The native protecting vegetation has been stripped aside, the natural rhythm of succession altered. Healing can never take place. Long before the grass can grow tall to shade out the seral species, the mower roars across the landscape, cutting plants back to the ground. As far nature can tell, a lawn is a perennial war zone.

Every time you mow the lawn, putting the brakes on succession, you send a clear ecological message–a disaster has occurred! And how does nature react to catastrophe? What plants inevitably arrive, like medics, to heal the wounded earth?

The pattern repeats as it has for countless eons. Right after a disaster, nature sends in the marines, so to speak. The hardy pioneers invade the environment that they’re best suited to exploit. Humans have created an artificial habitat that is utterly ideal for seral species–like dandelions.

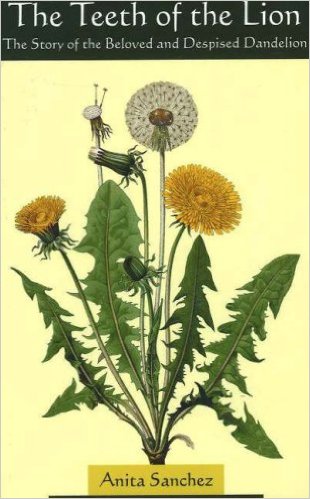

For more dandelion lore and ecology, please check out my book The Teeth of the Lion: The Story of the Beloved and Despised Dandelion.

For more dandelion lore and ecology, please check out my book The Teeth of the Lion: The Story of the Beloved and Despised Dandelion.

Recent Comments