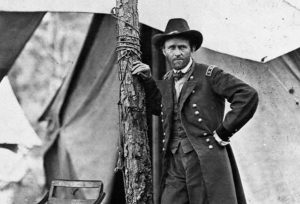

Ulysses S. Grant isn’t exactly a household word these days, but since the historical site known as Grant’s Cottage isn’t too far from where I live, I paid it a visit one sultry August afternoon. It’s not exactly a cottage, quite a nice big house, really, perched on the top of Mt. McGregor in the Adirondacks. Grant didn’t live there, he used it only once, as a brief author’s retreat for six weeks as he finished writing his first—and only—book.

Ulysses S. Grant isn’t exactly a household word these days, but since the historical site known as Grant’s Cottage isn’t too far from where I live, I paid it a visit one sultry August afternoon. It’s not exactly a cottage, quite a nice big house, really, perched on the top of Mt. McGregor in the Adirondacks. Grant didn’t live there, he used it only once, as a brief author’s retreat for six weeks as he finished writing his first—and only—book.

Now you might not think of Ulysses S. Grant as a writer. He had several other careers, but as an author he’s not exactly on the New York Times best-seller list. And I have to confess that I haven’t been able to plow all the way through his book. I’ve sampled bits here and there, but The Personal Memoir of Ulysses S. Grant is a tough read. Two volumes long.

Grant certainly knew his subject, and he had some good stories to tell. But he wrote the book for what is usually the worst reason of all to write a book: money.

Grant had been a famous and wealthy man, a victorious general and even President. But he was a trusting innocent when it came to finances. Late in life, he fell for a plausible Ponzi scheme and lost every penny. And only weeks later, he was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer. Grant knew that his wife and children would be left destitute, and was desperate to do something to provide for them. His old friend Mark Twain, who was a publisher as well as a writer, offered Grant a $10,000 advance if he would write his memoirs.

Knowing he had only weeks to live, Grant began to write. And here’s the amazing part: he didn’t just do a quick knock-off job, as he surely could have been pardoned for, under the circumstances. Nope, General Grant was going to do it right. He worked on the book for hours every day in his New York City home, but the heat and the air pollution aggravated his symptoms. A friend offered him an escape: a cabin in the woods. Every author’s dream. A quiet little place to write, in the sharp, clean Adirondack air.

Grant barely made it to the cottage on the top of the mountain—a pleasant drive today, an arduous journey by carriage up steep winding roads then. He arrived exhausted, but soldiered on. His throat made it painful to lie in bed, so at night he wrote sitting up in a padded leather armchair with his legs propped up on the chair opposite. By day, he wrote sitting on the porch. For six weeks, he labored on. Surely he must have been tempted to say (as all authors are), “Oh, hell, that’s good enough, I’m done with the damned thing.” But he kept at it, knowing that he was on a tight deadline.

He wrote his way th rough the Mexican War, which he recognized clearly for the shameless land grab it was: “One of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.”

rough the Mexican War, which he recognized clearly for the shameless land grab it was: “One of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.”

He wrote all the way through the Civil War, not in the flowery, bombastic style of most Victorian writers, but in straightforward prose. He recounted the famous surrender at Appomattox, where he so enjoyed reminiscing with Lee over the old days that he almost forgot the purpose of their meeting. Grant was a good winner. “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

It’s odd that someone who was such a brilliantly successful general was such an appallingly bad president. He’d learned a bit, though, from his long and eventful life: “Experience has taught me two lessons: first, that things are seen plainer after the events have occurred; second, that the most confident critics are generally those who know the least about the matter criticised.”

Finally, finally, he was done. He died four days after writing the final words.

The book was a smash hit, Twain’s canny marketing plans being very successful. If there had been a New York Times best-seller list in those days, Grant would have topped it for the next two years. His family received almost half a million dollars in royalties, worth many millions in today’s money.

Grant had little time for appreciating the beauties of nature in his desperate sprint to finish the book, but the peace and calm of the mountains seems to have soothed him. On one of his last days, he asked to be taken in a wheeled cart to a nearby overlook. In the clear air, you can see fifty miles across the Hudson Valley. Grant sat and contemplated the view for a long time. In this most peaceful of places he wrote the tale of America’s bloodiest war.

Grant closed the book with a surprising note of optimism that “Federal and Confederate” would someday be able to reconcile. “I cannot stay to be a living witness to the correctness of this prophecy; but I feel it within me that it is to be so. The universally kind feeling expressed for me at a time when it was supposed that each day would prove my last, seemed to me the beginning of the answer to “Let us have peace.”

2 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Unmowed Authors - […] Ulysses S. Grant […]

Anita, this is a fascinating and informative peace.

You seem to have caught the peace of the place and the metal of the man looking to satisfy family needs after he passed into the next realm

Thank you! Yes, it’s a very peaceful place. Didn’t see any poison ivy there.