When Laura Ingalls Wilder sent the manuscript of her latest prairie book to the publisher, they told her it would never sell. No children, they said, would want to read about “A Hard Winter.” They gave it the cheerier title of “The Long Winter” and put happy children throwing snowballs on the cover.

When Laura Ingalls Wilder sent the manuscript of her latest prairie book to the publisher, they told her it would never sell. No children, they said, would want to read about “A Hard Winter.” They gave it the cheerier title of “The Long Winter” and put happy children throwing snowballs on the cover.

But “the Hard Winter” was what all the folks who lived through it called the winter of 1880-1881. Of all Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books, this is the one with the least fiction; her unvarnished description of that bone-chilling winter is drawn from life. Monster blizzards struck every few days, and the thermometer hit forty degrees below zero. And that’s not counting wind chill.

The first blizzard surprised them in October, while the Ingalls family was living in a quickly-build shanty on their land claim in South Dakota. “Laura’s nose was cold. Only her nose was outside the quilts that she was huddled under…Ice crackled on the quilt where leaking rain had fallen. Winds howled around the shanty and from the roof and all the walls came a sound of scouring. Snow had blown under the door and across the floor and every nail in the walls was white with frost.”

And then things got bad.

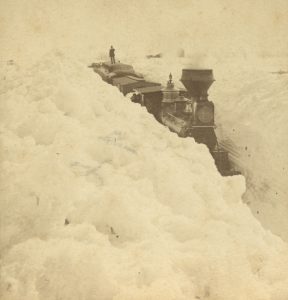

The snow was so deep that it blocked the railroad tracks from Christmas to April. The little town of De Smet (pop. 80) was cut off from the rest of the world. With no supply trains, coal soon ran out. On the all but treeless prairie, there wasn’t much to use for fuel. Families burned fenceposts, furniture, and sticks of twisted hay to keep warm. Then food ran low, and since Pa hadn’t had much success with his crops, the Ingalls were soon hungry. At one point they were down to six potatoes, one for each of them.

After the first blizzard, the family had moved to the nearby town, where there was a solid wooden building that Pa had built to rent out as a store.  The building is long gone, but this red brick law office is on the very spot where the Ingalls family shivered through the Hard Winter. Often the blowing snow was so thick that they couldn’t see Fuller’s Store across the street. At one point the whole town was buried up to the roofs. This turned out to be a good thing, since the house was much more cozy protected from the raging winds, and Pa could walk through a snow tunnel to the stables to feed the horses.

The building is long gone, but this red brick law office is on the very spot where the Ingalls family shivered through the Hard Winter. Often the blowing snow was so thick that they couldn’t see Fuller’s Store across the street. At one point the whole town was buried up to the roofs. This turned out to be a good thing, since the house was much more cozy protected from the raging winds, and Pa could walk through a snow tunnel to the stables to feed the horses.

“There’s only this month, then February is a short month, and March will be spring,” Pa says cheerily. But by April, the blizzards were still pounding the little house.

“The fire must not go out; it was very cold. They ate some coarse brown bread. Then Laura crawled into the cold bed and shivered until she grew warm enough to sleep.”

No wonder even Laura sometimes pushed the snooze button and went back under the quilts.

Recent Comments