A fairy ring appears magically overnight—a circle of mushrooms sprouting from the grass. Plainly, some magic is at work. Does it mark the spot where fairies or witches were cavorting till dawn?*

A fairy ring appears magically overnight—a circle of mushrooms sprouting from the grass. Plainly, some magic is at work. Does it mark the spot where fairies or witches were cavorting till dawn?*

I stood within the circle of the fairy ring and looked out over the Sussex hills and meadows. It’s a landscape that lends itself to thoughts of magic. There’s a legend that this was the last place in England where fairies remained.

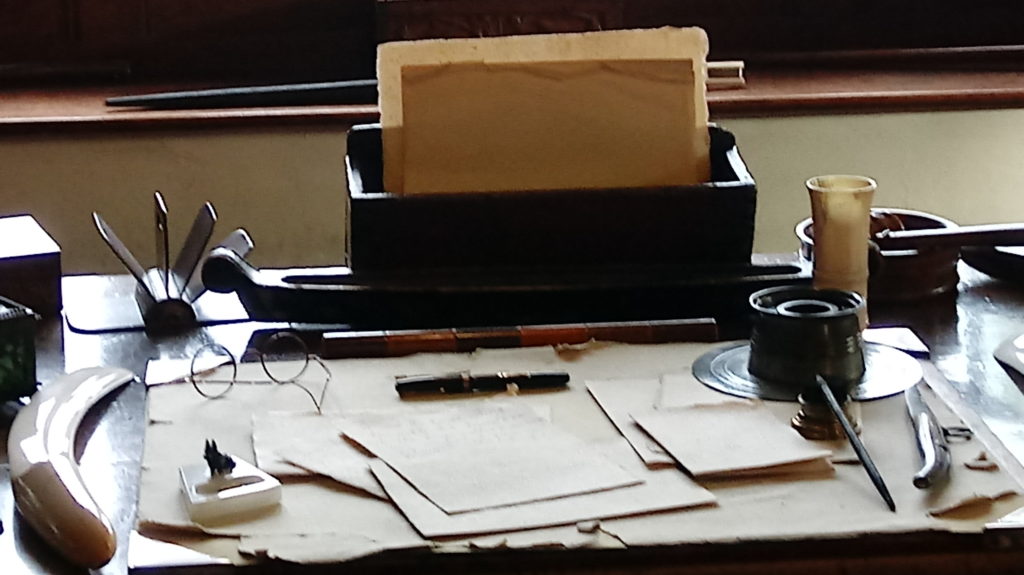

Rudyard Kipling was fascinated by this soft green landscape of gentle hills and little rivers. And the old stone house, known as Bateman’s after the original builder, enchanted Kipling from the moment he laid eyes on it. He and his wife bought the property, including a seventeenth-century manor house made of mellow old stone, barns and stables, and a small watermill, in 1902. He lived there for the rest of his life.

It was all nestled deep in a valley, guarded by oaks hundreds of years old. Bateman’s was a perfect place to hide. Kipling was one of the few lucky authors who hit it big with his first book and became famous in his youth. By this point in his life, in his late thirties, he was a national celebrity. Kipling was so admired and sought-after that in other places he’d lived, fans would peek in his windows hoping to get a glimpse of the famous author at work. So Bateman’s was a place of refuge, far off the beaten track; here he could have peace and privacy.

The orchards, hedges, and meadows of Bateman’s were also a place to heal. Kipling was still reeling from the most devastating blow of his life, his daughter Josephine’s death from fever at the age of six. Kipling was a devoted, loving father who was deeply invested in his children (unusual in a time when fathers and mothers often left the care of the kids to the nannies.) He played with them, hung out with them, and told them stories—stories which of course have delighted millions of children for generations, like the Jungle Book tales, and the Just-So Stories.

Bateman’s was, above all, a wonderful place to play. Here Kipling recovered his energy and joy while exploring the woods and fields with his two remaining children, Elsie and John. They spent hours boating on the river, getting to know the cows and sheep in the farmers’ pastures, and creating imaginary kingdoms among the fields, barns, and streams.

“They were fishing, a few days later, in the bed of the brook that for centuries had cut deep into the soft valley soil. The trees closing overhead made long tunnels through which the sunshine worked in blobs and patches. Down in the tunnels were bars of sand and gravel, old roots and trunks covered with moss or painted red by the irony water; foxgloves growing lean and pale towards the light; clumps of fern and thirsty shy flowers who could not live away from moisture and shade. In the pools you could see the wave thrown up by the trouts as they charged hither and yon, and the pools were joined to each other—except in flood-time, when all was one brown rush—by sheets of thin broken water that poured themselves chuckling round the darkness of the next bend. This was one of the children’s most secret hunting-grounds…”

Kipling was in some ways a foreigner in his own country. He was born in India and spent much time there, and had lived in America and other countries before settling in Sussex. He became fascinated with the rich history of this corner of the southeast of England. Here at Bateman’s he wrote my favorite of his works, the all-but-forgotten children’s classics Puck of Pook’s Hill and its sequel Rewards and Fairies.

It’s seldom remembered nowadays that Kipling originated the genre of books where realistic children stumble into magic adventure. He created the idea of ordinary kids minding their own ordinary business—and suddenly the world of magic intersects with their everyday life—turns out there’s a snowstorm going on in the back of a wardrobe, or an owl brings you a letter inviting you to Hogwarts! He was followed by E. Nesbit, Edward Eager, C.S. Lewis’s tales of Narnia and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter. But Kipling did it first.

Dan and Una (John and Elsie) step inside a fairy ring to trigger the magic. They meet Puck, the ancient sprite of the hills, and he introduces them to a series of characters from England’s past: a Roman centurion, an Anglo-Saxon Monk, a Norman knight, smugglers, pirates, Queen Elizabeth herself. These fantasies rooted in history, filled with tales and legends about old England, are among the best writing Kipling ever did.

See you the dimpled track that runs

All hollow through the wheat?

O that was where they hauled the guns

That smote King Philip’s fleet.

See you our little mill that clacks,

So busy by the brook?

She has ground her corn and paid her

Ever since Domesday Book.

See you our stilly woods of oak,

And the dread ditch beside?

O that was where the Saxons broke

On the day that Harold died.

…

And see you after rain, the trace

Of mound and ditch and wall?

O that was a Legion’s camping-place,

When Caesar sailed from Gaul.

And see you marks that show and fade,

Like shadows on the Downs?

O they are the lines the Flint Men made,

To guard their wondrous towns.

She is not any common Earth,

Water or wood or air,

But Merlin’s Isle of Gramarye,

Where you and I will fare!

–Rudyard Kipling

*Actually, a fairy ring is caused by a mushroom sending rootlike structures called mycelia outwards in all directions. The central mushroom eventually dies, but the ring keeps sending mycelia outwards, and new mushrooms pop up in a circle. Mushrooms often spring up with magical-seeming quickness after a rain. Fairy rings widen over years, decades, perhaps even centuries.

Recent Comments