Welcome to the world of puddles!

There’s nothing shallow about a puddle. It’s an often-ignored but crucial habitat for countless wildlife, including frogs, birds, and butterflies. Hello, Puddle! helps children understand the intricate, unnoticed links between animals and their habitat.

As an educator, you can use the book–and real puddles just outside your door–to teach students about science, language arts, and the wonders of the natural world.

photo by Steve Bonn

Contents

–Why Puddles?

–Earth Science Activities

–Math Activities

–Life Science Activities

–Language Arts Activities

Why Puddles?

Puddles are homes, bathtubs, and drinking fountains for wildlife. They also provide a key ingredient for many animal homes: mud!

–Birds grab beakfuls of puddle mud for nest building. Declines in populations of some birds, like barn swallows, are directly linked to lack of a readily available source of mud for nesting.

–Robins love to splash in puddles, and frequent baths keep feathers in peak flying condition.

–Frogs use puddles for mating and egg-laying. Temporary puddles are especially crucial habitat for American toads.

–Butterflies engage in a behavior called “puddling” where they sip not only water but nutrients found in mud.

The Science of Puddles

Next Generation Science Standards

Hello, Puddle! aligns strongly with the Disciplinary Core Ideas of the Next Generation Science Standards, especially focusing on three of the Science Standards for K to Grade 2:

2-LS4-1: Make observations of plants and animals to compare the diversity of life in different habitats.

The book shows the diverse habitats that organisms can thrive in: urban lots well as lawns and meadows.

K-ESS3-1: Understand relationships between the needs of different plants and animals (including humans) and the places they live.

The book stresses the relationships between animals and their environment. Puddles are part of a complex web of interrelationships with many species of insects, mammals, and songbirds.

K-LS1-1: Use observations to describe patterns of what plants and animals (including humans) need to survive.

The book encourages first-hand observation of nature, and is meant to inspire students to make their own observations.

Common Core State Standards on Science Literacy

A strong focus of Common Core is the concept of life cycles. (CCSS.ELA standards Domain 6: Cycles in Nature.) The book follows wildlife through the seasons, and emphasizes the concept of seasonal changes.

In line with the strong Common Core emphasis on reading informational texts, the book introduces biological concepts such as interrelationships and life cycles. (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.4: Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words or phrases in a relevant text.)

Earth Science Activities

Why is there a puddle in this particular spot? Puddles form where they do because of the shape of the soil or pavement beneath them, and the slope of the land. Puddle-watching is a good way to introduce young students to some basic concepts of earth science.

–Ask students to theorize why the puddle is there. Is there a drip from a nearby roof? Maybe a tree shaded the ground, so the water did not dry up. Is there a depression in the ground, caused by people walking? Is it at the bottom of a slope? Has the soil been eroded, or worn away, by wind or water or human activity?

–Look over the schoolyard and have the students predict where puddles might form next time it rains. Note their predictions and see if they’re accurate next time there’s a shower.

Mud

The shallow water of a puddle seeping into the soil creates something a lot of animals can’t live without: Mud.

Robins and barn swallows use the damp soil from puddles as a form of cement to help to build their nests. But here’s the problem—there aren’t as many puddles as there used to be! Dirt roads, farmers’ fields and back yards used to be perfect places for puddles. Now most roads and driveways are paved, and lawns cover up most of the soil.

And not every puddle is good for wildlife. A puddle in a blacktop driveway, with a rainbow of oil on the water, is no place for animals to drink, or for you to splash in.

–Have each student collect some mud, using a popsicle stick and a small paper bag. If it’s too dry for mud, you’ll have to make some–pour water onto some soil and stir it up a bit.

Take the mud back inside the classroom to examine it up close. Have each student spread out their mud sample on a paper towel. (The paper towel will soak up the excess water to prevent drips.)

Observe what mud is made of. Tiny specks of soil, bits of gravel, chunks of rock. Anything else? Mud is composed of bits of broken rock mixed with organic matter. Organic means something that was once alive. There will be tiny bits of plants, leaves, grass, and other materials mixed in with the rock. Soil isn’t just dirt–it’s a complicated blend of rock particles and organic matter, containing the nutrients that plants need to grow, and that butterflies need, too.

photo by Greg Dajewski

Math Activities

Use basic math skills and simple tools to explore the puddle.

–How deep is the puddle? Measure depth using a ruler. Is it the same depth everywhere, or are there deeper spots?

–How wide is the puddle at the widest part? How long? If it’s a big puddle, students may need to work together using a tape-measure or a piece of string.

–Record the measurements, and then re-take them several times over the course of several days. Does the puddle get bigger, stay the same size, or shrink?

–Keep an eye on the puddle, perhaps checking it once a week. Keep track of the temperature. Does the puddle get smaller as the temperature goes up?

Ask students to predict what will happen to the puddle as the weather changes and the temperature goes up and down. Can you keep recording data on the puddle all year long? Or does it come and go with the seasons?

Life Science Activities

Encourage your students to observe any kind of wildlife, no matter how small, that use puddles. Insects, for example, will often lay eggs in shallow puddles. Snails and slugs like the moist soil that keeps their skin from drying out. And butterflies are huge fans of puddles. They sip water, and also drink up nutrients and minerals found in the soil.

–Watch birds bathing in puddles. It’s a lot of fun—both for the human watchers and also for the birds! Birds love a good bath, and really seem to be enjoying themselves, but it’s not only for fun. Clean feathers help them fly their best when it’s time to find food—or dodge a predator!

Puddles in schoolyards, driveways or parks can be opportunities to observe birds carefully. Do they wade in, or stand at the edge? Do they take a drink before bathing? What’s their bathing style? Most birds fluff their feathers so the water can reach their skin. They splash and flick the water all over their bodies, using their wings and dipping their heads. Some birds, like swallows, take baths on the wing, dipping into the water and then skimming out again.

Birds bathe more often than most people do! On a hot summer day, a chickadee might take as many as five baths a day. They’ll even bathe in wintertime, since it’s so important to keep feathers in top flying condition.

photo by Brian Henderson

–Keep a class checklist of any animals your students observe in or near the puddle–no matter how small. If you’re not sure of the species name, describe the animal: “small yellow bird,” or “tiny insect that floats on surface.” More important than naming it correctly is observing the animal closely. Ask students open-ended questions like, “What color is it?” or “What do you think it’s doing?”

–Have students to imagine how a bird would make a nest from mud. Birds mostly use their beaks for nest-building. Have the students use sticky mud (or play-dough) to create a small nest, using bits of dried grass or sticks.

A Puddle is a Safe Home

Since puddles often evaporate in summer or freeze solid in winter, that means nothing can live in them permanently. That means no fish.

Fish often eat young frogs, salamanders, and insects. So a shallow puddle means no predators and is a safe place for these creatures to hang out.

Animals like salamanders, wood frogs, and fairy shrimp depend exclusively on forest puddles, known as vernal pools, for part of their life cycles. Often a pool is the ancestral home of an amphibian community that lives nearby and migrates to the same pool each spring to lay eggs.

–Examine puddles in spring for tiny creatures. Scoop up a sample of puddle water, and put it in a clear glass jar as a mini-aquarium. Observe it carefully for signs of life. Sometimes what appear to be floating specks of dirt are actually tiny creatures swimming along. Don’t forget to return the sample to the puddle when you’re done!

–Make a chart of the life cycles of puddle creatures. Some, like snails, hatch from eggs and grow bigger without changing their shape. But many puddle creatures like toads, dragonflies, or salamanders, go through a process called metamorphosis, changing their shape as they grow to adulthood.

Language Arts Activities for Hello, Puddle!

Check out Patricia Newman’s LitLinx blog for many wonderful ideas from nonfiction authors on combining STEM and language arts in your curriculum: LitLinks highlights the natural connection between STEM & language arts (patriciamnewman.com)

Splashing in the Puddle: Verbs

The hardest kind of writing is to write short. Hello, Puddle is the shortest book I’ve ever written, but it was also the most challenging.

In order to engage the youngest readers, I wanted to use as few words as possible to describe the action, so the main text on each page is only a few words. Sometimes it’s two words. Noun, verb. That’s it. Other pages have two verbs that help each other—like scratch and dig, or splish and splash.

For older students, there is also supplementary text explaining the wildlife science in more detail. But to engage the youngest readers in this book, I used only a few words for the main text. So the verbs I chose had a lot of work to do.

Verbs are Doing Words (Activity for pre-K -Grade 1)

Introduce your students to the idea of verbs—words that are about doing things. Verbs describe action, and often (not always) your students can act out what they mean. If you say the verb “hop,” for example, they can hop. Have the students practice acting out action words, like bend, blink, or stretch. (Avoid verbs that are too active!)

Then read the text of Hello Puddle, asking students to raise their hand each time they hear a verb. As you read, share the illustrations by Colombian artist Luisa Uribe. Have students point out places where the animals mentioned in the text are doing the action the verb describes. Look for the butterflies feasting, the deer sipping, and the robin splashing.

Then read the text again, and have students act out the verbs—allow some room to move! Students can use their imaginations as they scoop mud like a mud-dauber wasp, or loop-the-loop like the swallows.

Choosing the Right Word (Activity for Grade 1-3)

It took a lot of thought to select just the right verb for each animal. I spent the most time pondering a word to describe exactly how ducks feed in a puddle. Mallards and other species of ducks known as dabbling ducks use their beaks like strainers. They take a gulp of water but don’t swallow it—they sort of chew it with their beaks, which squirts out the extra water and leaves the tiny plants and bugs which they use for food. And ducklings, with their tiny beaks, take little, delicate sips of water. Ducklings munch? Ducklings slurp? I finally settled on nibble.

Ask your students to think of verbs that can describe an action with one word instead of many. How else could they say “He ran very fast?” (He sped, he raced, he zoomed.) How else to say “She ate a lot of food in a short time?” (She gobbled, she stuffed.)

Go outdoors into the schoolyard, playground, or a nearby park. Each time you spot a plant or animal, say the noun and ask students to come up with one verb that describes what the organism is doing. You don’t need to identify the creature or plant precisely—general terms like leaf, bug, or bird are fine. Here are some possibilities created by one class of first-graders:

Leaves rustle, wiggle, shine

Bug buzzes, zooms, bugs me!

Bird flies, flaps, runs away (some actions need two or three words, like loop-the-loop.)

Ask students to count the number of words in the main text of Hello, Puddle (not including the supplemental text in smaller print.) It’s not a big number—it only takes a few words to write a book. But it’s hard to choose which ones!

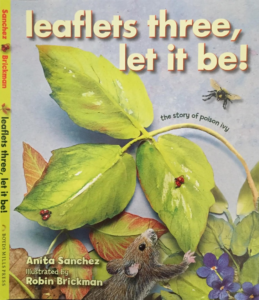

For more information on plants and animals in the backyard habitat, please check out my book Leaflets Three, Let it Be: The Story of Poison Ivy. Like a puddle, poison ivy is a rich habitat for unexpected wildlife!

For more information on plants and animals in the backyard habitat, please check out my book Leaflets Three, Let it Be: The Story of Poison Ivy. Like a puddle, poison ivy is a rich habitat for unexpected wildlife!

Recent Comments