Once you start looking, you notice them almost everywhere you walk. On trees. On rock walls. On stumps and tombstones and trees. They look like spatters of grayish-blue-green paint spattered over the trees and stones: the dried-up, twisted forms of lichens.

Once you start looking, you notice them almost everywhere you walk. On trees. On rock walls. On stumps and tombstones and trees. They look like spatters of grayish-blue-green paint spattered over the trees and stones: the dried-up, twisted forms of lichens.

What is a lichen, anyway? It’s actually two things, two distinct and unrelated organisms—a species of fungi and a species of algae—living together in a symbiotic relationship. It’s not that the fungi and the algae happen to be growing in the same place—they actually combine to form a whole new entity.

Lichens cling to surfaces with things that look like roots, called holdfasts. But holdfasts aren’t roots, as they don’t suck up any nutrients or water—they just let the lichen hold on tight. The algae creates food for both organisms, using sun, water, and air to make the sugars that nourish the pair of them. The fungus would starve without the algae’s photosynthesis.

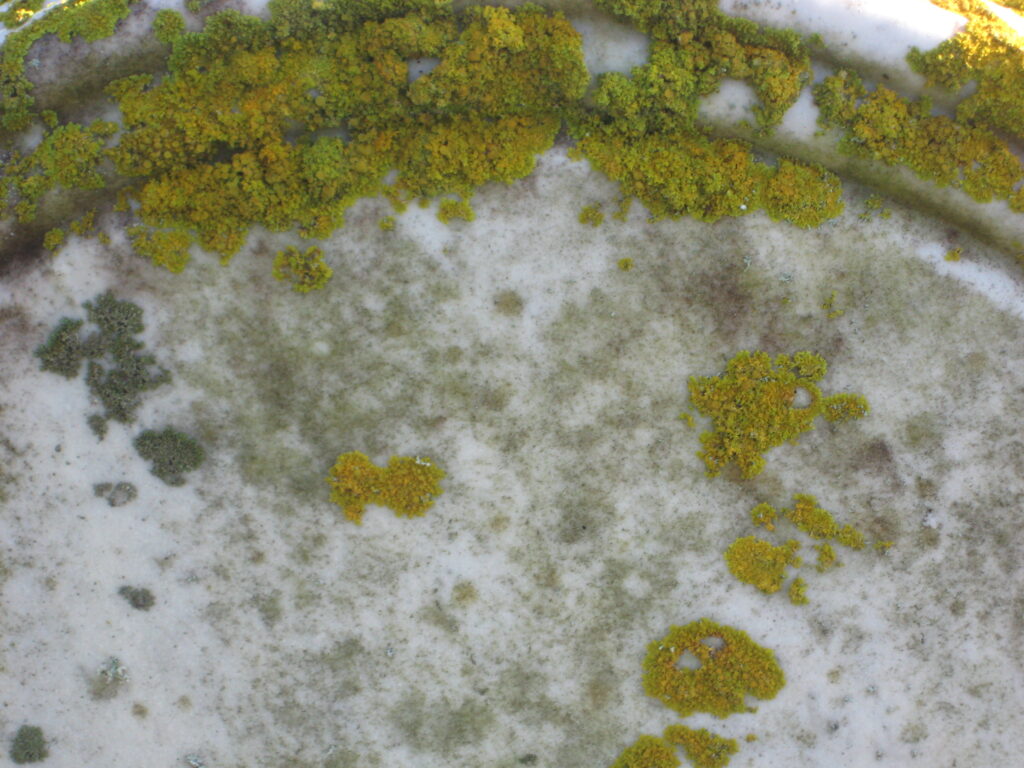

But like any good relationship, it’s a two-way street. The flimsy, moisture-loving algae wouldn’t stand a chance on dry, barren rocks or tree bark without the support and structure of the fungus. The fungal cells surround the algae completely—like an apple pie, so to speak, the crust being the fungus part, the fruit filling being the algae. Especially after a rain, you can see the green gleam of the plant shining through the thin fungus crust.

This intertwined lifestyle gives lichens a tremendous advantage. They can survive in the most inhospitable habitats you can imagine. There’s almost nowhere where lichens don’t grow—under the soil, on church steeples, on the back of a slow-moving tortoise. They’re a tiny touch of green in the Sahara. They’re the dominant species of vegetation in the Antarctic, where they live between snow crystals. They grow on the stone heads at Easter Island and on the top of Mount Marcy. Lichens especially love cemeteries. When you die, if you have a tombstone, there will probably be a lichen growing on it.

And of course there isn’t just one type of lichen, there are thousands of them, composed of various combinations of algae and fungi. Different species occupy different niches—for instance, a lichen that needs more sunlight might grow on top of a branch, while one that prefers moisture and shade might grow on the underside of the same branch.

Most types of land plants have a waxy coating called a cuticle on their leaves. This covering functions almost like our skin, keeping moisture in and infections out. Lichens don’t have this protective layer. Lacking a cuticle, lichens can absorb every speck of moisture before it trickles away, a big advantage when living in an arid spot like the side of a boulder. But lichens are essentially living blotters that soak up everything they come in contact with. Unfortunately for lichens, this includes pollutants in the air.

This permeability makes lichens highly susceptible to air pollution. Where smog and pollutants rise from cars and factories, lichens vanish.

Scientists have been using lichens as handy, free bio-monitors since the 1800s. Lichens are the proverbial canary in the coal mine. Like the dead canary, the absence of lichens is a cry of warning—nature’s subtle smoke alarm.

Here the air is fresh and clear. The lichens tell us so.

It was so lovely and refreshing to learn about healthy lichen being a sign of clean air when I moved to the Pacific NW–given how abundant and glorious the lichens are on the trees in my garden and on any local hike!

The Pacific Northwest is so incredibly gorgeous!

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!!

Finally I’ve found something which helped me.

Thank you!

Prego!