Much of the Irish coast is harsh, with steep, stony cliffs and rock-filled coves. The North Sea water is bitter cold. But during the terrible winter of 1846, starving people waded into the icy waves, desperately scooping up seaweed. People scrambled over rocks scoured by powerful waves, clinging to the seaweed to hang on as water washed over them. But they knew that seaweed could mean the difference between life and death.

In autumn of the year before, the harvest in Ireland had been a good one. The barns and bins used by Irish farmers to store their yearly crop of potatoes were filled. For decades, the people of Ireland had depended on easy-to-grow, nutritious potatoes as their main food source. But that fall, something dreadful happened. Their harvest began to melt away before their eyes.

The potatoes started to turn black. Then they liquified, turning in a few minutes to a foul-smelling black goo as farmers watched in horror. At first it seemed like some evil magic was at work, but soon they realized that the cause of the disaster was a fungus that infested the potato fields. Half the potato crop failed that year, and most of the potatoes died in following years. A terrible famine descended on Ireland.

With their staple crop vanished, people searched desperately for any possible source of food. Soon every scrap had been eaten. A million people died of malnutrition and starvation.

But some managed to survive by remembering the lore of past times. Potatoes, which originally came from South America, had been grown in Ireland for a hundred and fifty years. But long before potatoes arrived on Ireland, people had gotten food from the sea. Now in the depths of famine they found on the seashore a crop of nutritious food that their ancestors had eaten, a life-giving food the fungus couldn’t kill: seaweed.

Ireland’s rocky coast was a perfect place for seaweed to grow. Every rock below the high-tide line had a fringe of edible seaweeds: Irish moss, dulse, sea lettuce, kelp, wrack, and more. Seaweed was a free source of food during the famine, but it was a crop that was difficult and dangerous to harvest. As seaweed grew scarcer in shallow areas, people had to go out deeper. Some waded up to their necks, spending hours shivering in the bitter cold water. Others went further out in small boats, braving winds and treacherous North Sea storms. It wasn’t possible to gather huge amounts of seaweed under these conditions.

But even a few bites of seaweed can be a lifesaver. Even just a nibble of seaweed has lots of the essential vitamins and minerals humans need to keep us healthy. Many types of seaweed are so rich in nutrients that today we call them superfoods. Ounce for ounce, sea lettuce has more iron than spinach does. Dulse has more protein than eggs or steak. Kelp has more calcium than milk. And seaweeds are high in vitamins—some kinds of seaweed have more vitamin C than orange juice.

Seaweed is especially high in what are called trace minerals. These are essential minerals that the human body must have to be healthy, but they’re only needed in very small amounts: unfamiliar substances like iodine, molybdenum, zinc, and chromium. Nowadays we don’t worry about them since it’s easy to get all our trace minerals from vitamin pills or fortified foods like breakfast cereals. But before the twentieth century, it was very difficult for people, especially the poor, to get these life-giving nutrients.

Sadly, seaweed couldn’t cure the tragedy of the Potato Famine. For one thing, seaweed doesn’t have a lot of calories, which give you energy—you can’t survive for long living only on seaweed. But adding seaweed to their diet must have saved many thousands of people from some of the terrible effects of malnutrition.

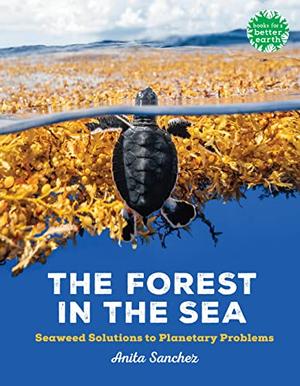

For more about seaweed, please check out my book The Forest in the Sea.

Recent Comments